The Irish backstop explained and the implications for businesses

Posted: Thu 24th Jan 2019

The so-called Irish backstop is dominating the Brexit debate. Sietske de Groot, founder of TradePeers, explains what it is and what it means for businesses.

In Brexit parlance, 'backstop' means "a legal guarantee that there will be no border between the Republic of Ireland (RoI) and Northern Ireland (NI)".

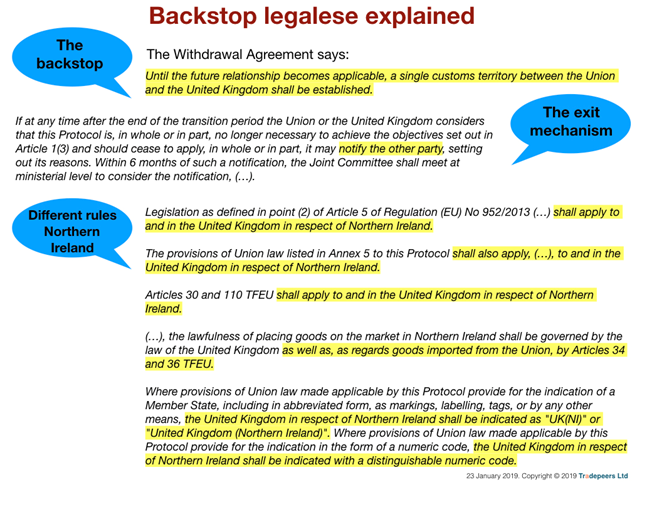

The issue is technical, hypothetical, and foremost, political. It is holding up parliamentary approval of the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement, or the 'deal', that contains the text of the backstop (see image below).

What does the backstop do and what does it mean for businesses in the UK?

When the country leaves the EU, the UK will have its own laws and tariffs that apply to products coming into the UK from the rest of the world. They can differ from EU tariffs and laws for products coming into the EU.

Therefore, a separation between the European market and the UK market to allow the correct tariffs to be applied and compliance with the correct rules to be checked, may be necessary.

However, the 1998 Belfast Agreement, the treaty between Ireland and the UK, prohibits a border between NI and the RoI. This agreement is based on both countries being a member of the EU, a single regulatory and customs area. But the UK's departure from the bloc was not anticipated.

The challenge now is to find a post-Brexit customs arrangement in which UK and EU rules and tariffs can co-exist without the need for a border on the island of Ireland.

This puzzle is for the EU and UK negotiators to solve when they start discussing a trade deal. Talks will start as soon as the Withdrawal Agreement has gone through Parliament.

However, it is not sure whether they will be able to agree a borderless customs arrangement before the current set-up expires on 31 December 2020. For as long as this is not the case after that date, the UK will have to stay within the EU customs territory.

This is what is called the 'backstop'. It prevents a border on the island of Ireland because the UK will continue to apply EU rules and tariffs to imports from the rest of the world.

However, there are two problems with this solution.

Problems with the backstop

First, the UK could stay permanently in a single customs territory with the EU. Therefore, some MPs demand a legal guarantee that the backstop is temporary and that the UK can leave the EU customs territory of its own accord.

The EU is concerned that if the UK does so, it will instate different tariffs and different rules on imports from the rest of the world. This would create unfair competition between the EU and the UK markets. For example, the UK could have lower import tariffs on olives.

They would come into the UK via the ports in Northern Ireland and could flood the EU market if there is no border with Ireland. In the same vein, potentially different hygiene standards could divert trade to the UK, and meat or other food products could find their way to Europe via Northern Ireland, or so the EU fears.

A border between Ireland and Northern Ireland would be necessary to protect the EU single market from unfair competition, but this goes against the Belfast Agreement. The solution is to have the same rules and tariffs on both sides. The backstop is the legal guarantee for that.

Second, if the backstop is activated, Northern Ireland will be treated differently when it comes to regulation. As it has an open border with the European market, Northern Ireland will have to apply more EU rules than the rest of the UK.

Great Britain's (GB) only entry points to the EU are ports. Hence it cannot oversupply the EU market with products that are cheaper to import and that are regulated differently. Therefore, it will only be in a bare-bones single customs territory with the EU, with zero tariffs on all products and only some EU rules to apply where they are relevant for cross-border trade.

Legal changes to the text on the backstop in the Withdrawal Agreement are entirely possible, but are dependent on political will and trust.

The EU has to trust the UK that it will not engage in anti-competitive behaviour, which may result in a hard border and potentially violates the Belfast Agreement. The UK has to trust the EU that it will not keep the UK in the single customs territory ad nauseum.

What the Irish backstop would mean for businesses

Now back to business. The backstop is theoretical and will only happen if the Withdrawal Agreement is agreed by Parliament and if the EU and the UK didn't manage to find a borderless customs solution during their trade talks.

In that event the backstop will be activated in 2021 and businesses in NI can export to the EU and trade with GB as they do now. GB businesses can continue to export to the EU and trade with NI, but some compliance checks with EU rules may be necessary at the ports for UK-NI/EU trade.

If there is no deal, businesses in NI and GB can trade with each other as they do now. However, tariffs will have to be paid on UK-EU and EU-UK trade, and compliance checks with EU rules are possible at all ports and land borders.

The question is whether this is feasible, but there is no guarantee that checks and tariffs won't happen.

About Go Global

Kickstart your international trading with this free programme of support from Santander and Enterprise Nation. Take me to the international trade hub

Get business support right to your inbox

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive business tips, learn about new funding programmes, join upcoming events, take e-learning courses, and more.

Start your business journey today

Take the first step to successfully starting and growing your business.

Join for free